Date of Event: 6/11/2000

Canyon involved: Carrabeanga Canyon

Region: Kanangra (Blue Mountains)

Country: Australia

Submitted by: Tim Vollmer

Source: News media

Injury: Double fatality

Cause: Rappel error, Inadequate equipment, Hypothermia, Darkness, Group dynamics

Description of Event: In June 2000, two experienced members of the Newcastle University Mountaineering Club, Mark Charles and Steve Rogers, died while descending Carrabeanga Canyon.

The following report is from a feature article published in the Good Weekend magazine the following year. The reporter retraced the trip with an experienced canyon guide. He also included extensive details based on statements other group members provided to police following the tragedy.

—

On a crisp day in June last year, nine members of a university outdoors club set off on a weekend canyoning trip. Two would never return. Here, Matthew Moore unravels a tangled tale of the small errors and miscalculations that led to tragedy.

Death in the wilderness:

Background: It took the seven survivors of last year’s canyoning disaster three days to walk out of the wilderness, three days in which they discussed the tragedy and decided they would never publicly talk about it. In the 16 months since, they’ve stuck with their decision not to explain how the leaders of their trip perished in the night, on a rope, out of sight, their bodies later found lying in a shallow pool of water on a rock ledge by police rescuers.

Earlier this year, the Coroner in the NSW town of Bathurst investigated and decided no inquest was needed, satisfied that Mark Charles’s and Steve Rogers’ deaths were an accident that would never be completely explained. Canyoning experts have remained mystified about the details of the accident, struggling to understand the news reports at the time that the two most experienced people on the trip had somehow got caught on the same rope where they’d apparently died of hypothermia.

Although the group has declined to talk to the media or outsiders, they did talk to the police. In seven sworn statements, the survivors told a harrowing story of how their weekend adventure slowly turned into tragedy. They detailed a succession of mistakes and miscalculations, in themselves all quite minor, which when added together cost two lives and nearly took several more.

These accounts have now been made available to the Good Weekend by the Bathurst Coroner. They’ve allowed us to retrace the trip through the Kanagra wilderness in the southern Blue Mountains to try to piece together what happened. With professional guide Lucas Trihey (who has 20 years canyoning experience) and fellow climber and NSW Fire Brigade rescue instructor Mick Holton, Good Weekend abseiled into the canyon to prepare this account. We went in winter, as the group had done, and at the same time of day. We completed our final abseil at night, as they had done, giving ourselves the best chance of understanding what happened a year earlier…

By the time they’d left Christina’s Pizzeria in the northern Sydney suburb of Thornleigh, the nine canyoners were already running late. They’d stopped there for dinner on Friday night after driving 150 kilometres from Newcastle. And they still had a long haul before a very early start in the morning. All were students and ex-students of Newcastle University, in their twenties and early thirties, who’d signed up for a trip run by the university’s mountaineering club. The advertisement for the trip in the club’s newsletter, Watson, said: “10 to 12 June, contact Mark, grade medium. To celebrate the Queen’s Birthday we thought we’d visit the delightful Kanangra Boyd National Park. Saturday and Sunday will be an overnight dry canyon with more abseils than you can poke a piton at. Monday will be a spot of caving in Tuglow for those still feeling OK … Abseiling experience and decent fitness required.”

Kanangra Boyd National Park is in the southern part of the Blue Mountains wilderness, well away from the more frequented bushland surrounding the bed-and-breakfast belt around Katoomba, to the north-east. The Kanangra terrain is steeper and more inaccessible than almost anywhere in NSW.

On the Monday before they set out, Mark Charles and his good friend and club president Steve Rogers, both 25, hosted a skills night so the group could bone up on their abseiling techniques. Both were passionate climbers classified by the club as having intermediate abseiling and canyoning levels which allowed them to lead the trip and borrow all the climbing equipment they figured they’d need.

They were a mixed group. Steve Ahern was rated an intermediate-level canyoner while the club secretary, Sarah Warner, was also reasonably experienced, with more than 20 canyoning trips under her belt. After bushwalking and canyoning for six years, Claire Doherty was a lot more experienced than the other four. Andrew Bish, at 32 the oldest member of the group, had done a few smaller canyons but never been in such rugged country before. Simon Baker, Dan Weekes and visiting American student Jim Ching-Jen Wang had little experience.

In the past decade, canyoning has become a boom sport in the Blue Mountains, with adventurers poring over topographic maps searching for isolated valleys that might be hiding another pristine sliver of wilderness. To get to that wilderness you need only basic climbing equipment, because you normally start at the top and go down. You do that by tying a strong nylon tape, often seatbelt webbing, around a tree, threading a long rope through it and throwing the ends over the cliff. When the group has abseiled down this doubled rope, the rope is pulled through the tape sling from the bottom and the sling is left behind – this is known as a retrievable abseil.

It was after midnight by the time the group’s two cars pulled off the dirt road that runs across the Kanangra plateau and drove into the Boyd River camping area. It was close to freezing and the place was deserted. Rather than set up camp, they simply spread their sleeping bags under the awning of a shed.

Saturday dawned fine. Mark Charles woke them early and began dividing equipment into nine piles, each with a helmet, whistle, two karabiners, a climbing harness and an abseiling device. There were 3 ropes, each more than 50 metres long. After breakfast, Sarah Warner and Andrew Bish drove the group a few kilometres back the way they’d come the night before, to the trip’s starting point. Before they could set off, however, one of the cars had to be driven to the Kanagra Walls car park (about nine kilometres away), where they would exit on Sunday afternoon. None of the group had done the canyon before and none knew how long it would take, although their guidebook warned: “An early start is needed to get down the steep bit before camping.”

Nine is a big group to take canyoning, and with the shortest day of the year less than a fortnight away Steve Ahern was starting to worry that 10:30 was too late to start. Still, the walking was easy on a good trail through open heathland and gnarled snowgums, reminders that temperatures routinely drop to zero and below. The easy walking stopped when the track gave out after less than an hour and Charles needed his map and compass to guide them through thick scrub on the ridge that leads north-east to Carra Beanga Brook. For the next three or four hours, they struggled towards the headwaters of the creek, stumbling over loose rocks that shifted underfoot. It was flatter going but not much faster in the creek itself, with big ferns and fallen trees making progress slow.

It was after two – perhaps closer to four – when the moist undergrowth finally gave way to a dry, rocky cliff top and the huge Kanangra wilderness burst into view. They were perched at the top of the canyon, and gazed east across 60 kilometres of green-treed valleys capped with sandstone cliffs. Looking down, the creek disappeared over a sheer drop into a moist confusion of moss and fern. This is the point where the canyon starts: once that first abseil is done, it’s very tough to turn back.

Given the hour and the group’s slow progress, Sarah Warner was apprehensive. “Right from the start, Mark had made us all aware that we should try to get down the falls before night so that we could camp at the bottom rather than on the falls,” she told police later. She raised her concerns with Claire Doherty. And then she asked Rogers if he’d done another Kanangra canyon called Danae, which drops a similar distance. “I assumed he knew how long it would take to complete the abseiling down the falls,” she said.

Rogers didn’t. Their guidebook said they had “about 10 abseils” to get to the bottom. In fact, there are 16 – they had no chance of reaching the bottom before dark. But they had to keep moving to have a chance of sticking to their ambitious schedule, which required them to get back to their cars by Sunday night in order to use their caving permits on Monday.

Looking down into Carra Beanga Canyon, they could see the waterfall was not one long, sheer drop but a series of steps – although the tree canopy kept hidden any hint of what these steps might look like. Their first abseil took them out of the sun and into the moist undergrowth. It was colder there and some stopped to put on warmer clothes. But not Mark Charles. He was busy establishing a routine, anxious to keep the group moving.

Charles was the first one down each abseil. Once at the bottom, he’d find a tree that would serve as an anchor point for the next abseil and tie a length of climbing tape around it. The first few descents were straightforward and the group made steady progress. But as the light began to fade around 5 pm, so did the enthusiasm. Beneath the trees, they discovered some sloping ledges where they might have stopped but Charles and Rogers were pushing on, looking for somewhere big enough and flat enough to make camp.

On his first overnight abseiling trip, Baker was starting to worry: “The further we descended down the falls, the ledges became smaller and smaller. I was becoming concerned with the fact that it was getting late and it seemed like there was nowhere to stop.”

As the last of the light went, Doherty told Warner they should stop. They were hungry, it was getting colder and several members of the group were getting dangerously tired. The short walks between abseils were getting steeper and some struggled to keep their footing on the slippery gravel where a fall could be fatal. Although it was cold and dark, the moon was rising and Charles encouraged them to push on. Those with head-torches turned them on before they began their last major descent for the night.

Andrew Bish was increasingly distressed in terrain he called “rugged and dangerous … We abseiled over two pitches in the dark and found ourselves on two very narrow, cold and wet ledges. ‘By this stage I was very cold, tired, hungry and wet. I had no idea where I was.”

Following in their footsteps, we land on the same narrow ledge, a sliver of cliff and earth perched above a 50-metre drop. It’s about five metres long and slopes down to the left towards the waterfall, about six metres away. It’s more than a metre wide in parts but it feels less because it also slopes downhill. There’s only one tree, perhaps 15 centimetres wide at the base, where wood-boring insects have made their home. Still, it’s the most secure thing around and we tie ourselves and our rucksacks to it to avoid slipping off. With a light breeze blowing waterfall spray over us, we put on waterproof pants and jackets.

A year earlier, Mark Charles stood here and quickly tied one end of a rope to that little tree and threw the rest of it out into the dark. With a little more time, and a little more light, he might have managed to climb around to a much bigger tree just 20 metres to his right, away from the waterfall. There, he would have found a bunch of climbing tapes tied around its trunk, evidence of the route taken by most previous canyoners. But he was rushing to get his group somewhere safe, too busy to put on his waterproof clothing before he threaded the rope through his abseiling device and headed off.

The first three metres take you to another ledge about the same size as the one above, but wetter. The edge of this ledge drops steeply, about 70 degrees, for five metres before it becomes sharply vertical. Carra Beanga is known as a dry canyon, where wetsuits are not required, but the route Charles selected becomes wetter soon after the vertical section starts (see diagram at left). With the wind blowing spray onto him, Charles was wet by the time he got to the shallow pool more than 50 metres down. “Off rope,” he called when he reached the flat ground. His head-torch showed his search for a campsite was over. Stretching around him was a huge ledge some 40 metres long and 20 metres deep, covered in boulders but with plenty of room to light a fire and space for a group twice their size to spend the night in relative luxury. He dropped his rucksack there.

Above, and out of his sight, the rest of the party arrived on the ledges, half of them squeezed onto the top where it was drier, the rest forced to find space on the lower ledge. On the top ledge, Rogers and Warner tied two ropes together to form a retrievable abseil, threaded them through the same tape on the little tree that anchored Charles’s single rope and threw them over the cliff. They couldn’t see Charles, but they heard him shout for the next abseiler to follow. By then, close to 7 pm, some of the group were no longer up to it.

On the lower ledge, Claire Doherty could see things were getting bad. “I noticed Jim Wang was lying in the foetal position … [he] was shivering like crazy. I started to worry he may be in the early stages of hypothermia.”

Cold, hungry and wet, with some close to exhausted, no-one was keen to follow Charles and abseil into the unknown. “I got the impression that Pebie [Steven Rogers’ nickname] was reluctant to go first because he asked around for volunteers,” said Doherty. But no-one did, so Rogers headed off.

As he disappeared over the ledge, Doherty remembers him issuing one final instruction: “Let down the single rope [that Charles had used] when I get down to the bottom.”

Rogers had no idea that a safe camping spot lay at the end of this abseil and he wanted the single rope to set up the next abseil. It was to prove a critical error. Rogers fed the rope through his abseil device and moved easily down the steep five metres to the lower ledge, where the cliff becomes vertical. The next bit is wet and slippery but still straightforward. Then there’s a sharp indent in the rock face. Here, as your feet lose contact with the rock face, your rucksack pulls you suddenly backwards, dragging your feet up to where your head should be if you’re not wearing a chest sling. Rogers wasn’t.

From 10 metres below, Mark Charles would have watched Rogers reach a wet rock ledge that marks the end of the long vertical section. It’s slippery but quite flat. When we abseil down, it’s where we first stop. From there, the final bit of the descent is still steep but it’s a slope you can scramble down. Above Rogers, Andrew Bish felt the double rope and found it unweighted. “It’s slack, it feels like he’s off,” he reported, suggesting Rogers was standing on the ledge. Suddenly, the rope went tight again.

Almost certainly this was the moment when Rogers got hurt. The autopsy report revealed he’d suffered a serious wound in the back of his head, just below the helmet, some time before he died. It’s possible this happened on the way down to the ledge, if he’d slipped and somehow swung into the cliff face. But this doesn’t explain why Bish felt the rope go suddenly slack. More likely is-that as Rogers stood on that ledge, a falling rock, unseen in the dark, hit him in the back of the head. He was probably struck as he was looking down towards Charles, attempting to clear the bunched-up ends of the double rope that were found with him on his ledge when morning came. After abseiling down the same pitch, and standing on the same ledge, one of Good Weekend’s guides, Mick Holton, says he’s “almost certain” Rogers was hit by a falling rock, a conclusion he reached after accidentally dislodging a large rock himself.

They knew none of this on the ledges above, waiting for Charles to make the call to abseil. When the rope went suddenly tight, it was impossible for others to abseil down it. They grew confused by the shouts from below and the rope that stayed taut. They became uneasy.

“We were calling out, asking if we could abseil or not. I could hear a voice, which was definitely Mark’s, but I couldn’t understand the sentence he was saying,” Steve Ahern said.

For half an hour they shouted, their words muddied into incomprehension by the waterfall and reverberations from the surrounding cliffs.

“Every time we called out, Mark responded, but I could not make out what was being said. I thought Mark sounded troubled,” said Ahern. Rogers had been on the double rope perhaps half an hour when his best chance of rescue disappeared. Confused by the shouting and anxious to help in some way, the group untied the single unweighted rope Charles had used for his descent. They threw it over as Steve Rogers had instructed, but not before pondering the wisdom of doing so.

“I think Sarah may have indicated that she thought it was a bad idea in case something happened and the rest of us needed a rope to get down,” Dan Weekes said.

She was right. But at the time, still early in the evening, they were expecting to follow on the double rope Rogers was using. They assumed the shouts from below were part of the preparations for another abseil. With the spare rope gone, they got increasingly edgy. There was no chance to abseil down to investigate, and no-one attempted another technique known as Prusiking to descend the double rope far enough to get a clear view of what was happening 30 metres below.

Steve Ahern stood waiting for clearance to use the double rope, shouting slowly and clearly: “Can … we … abseil?” No, was the only response they could distinguish. So they waited. Hours passed. About 10.30 pm, Ahern and Warner tried to pull up enough slack to abseil down, but the rope was too tight. On their sloping ledges, and with nowhere for them all to tie onto, organising a rescue was hardly an option. Stuck there, wet and cold, some were struggling to look after themselves. And some were angry. They put their efforts into staying warm.

“We discussed the fact that perhaps Pebie and Mark had decided to sit the night out and wait for daylight,” said Doherty. “We decided that was the only thing we could do … I thought the double rope was now tight because they had locked it off or something.” Their ledges were too small to stretch out and they tried not to sleep for fear of rolling off. But, cold and exhausted, they dozed though the night before dawn broke.

“We were expecting Mark or Steve to call out, but there was nothing. By 8am we got really worried,” said Simon Baker.

Bish leaned out from his ledge, hoping for a glimpse of either of the group’s two leaders. He saw nothing. He tried again, this time aided by a Prusik sling (loops of thin ropes) which he attached to the double rope. This allowed him to lean out far enough to see the first hint of trouble: “I could see a red backpack lying on the ground and half of the single rope lying between the pack, with some in the water.”

Leaving an uncoiled rope lying in the water was right out of character for experienced climbers like Charles and Rogers. Also using Prusik slings, that allow climbers to ascend and descend climbing ropes, Ahern then came down from the top ledge. He managed to climb down past the overhang where the double rope was pulled tight against the rock. Leaning out, he saw the two men about 30 metres below, both upside down and attached to the rope. Rogers was still wearing his rucksack. Ahern headed back up to the ledge and turned to Warner.

“I could see from his face that something was wrong,” she said. “He was quiet for a while and he said, ‘They are tangled together.'”

No-one can know for sure what happened down below. But it’s certain that Charles died attempting to rescue his mate. He climbed up to the ledge, probably straight after Rogers was injured, perhaps aided by the single rope before it was thrown down by the group above. He did so quickly, not bothering to get more clothing from his rucksack. When he got there, he stood on the ledge. He then secured himself by looping a Prusik sling, connected to his harness, around the double rope just above the point it was threaded through Rogers’ abseil device. Wet and freezing, Charles died attempting a courageous rescue. He was unable to get Rogers down those last 10 metres. Cold water can quickly make hands as clumsy as clubs. It’s possible Charles was unable even to get himself down, that he became trapped on the rope once his fingers could no longer undo his sling. And it’s also possible he simply refused to leave his friend alone in such a bleak spot.

The autopsy report says Charles’s death was due to hypothermia, but doesn’t pinpoint the time more precisely than between 6.30 pm and when he was found in the morning. Two of the party believe they heard him call out in the early hours of the morning although several experts believe it unlikely he could have survived until then.

The report on Rogers says his cause of death was “not clear” at the time of the autopsy. While hypothermia was a cause, it says “the possibility of perimortem head injury and/or mechanical asphyxiation are difficult to exclude”.

Steve Ahern was in shock when he told Warner what he’d seen. But as the strongest climber in the group, he took control. Using his two Prusik slings, he climbed slowly back down the rope, worked his way past the overhang and down to the ledge. He found his friends lying backwards, suspended less than a metre above the ledge they’d been standing on. Charles was on top of Rogers, whose helmet was touching the ledge. He called out their names as he slapped them, hoping for a sign of life, hoping to revive them, desperate to get them to safety so close below.

Ahern then assumed leadership of the group. Six friends were still trapped above him. It was early Sunday morning and no-one would begin to miss them until late Monday night. He cut the Prusik cords attaching Charles to the double rope, undid Rogers’ abseiling device and both bodies slumped onto the ledge.

He tried to move them but they were too heavy and he used his whistle to call Andrew Bish to abseil down and help him. Together they tried to move the bodies out of the way so the others would not have to see them, but they stopped when they realised they were too heavy and they might easily fall themselves. One by one, the others came down, each of them passing by their dead friends, each of them distressed at what they saw.

It was close to lunchtime when they began their long trek out. They didn’t know it then but they still had about nine abseils to do, some of them in tricky spots, over ledges loaded with loose rocks or in places too cramped for more than a couple of people to wait.

By dusk on Sunday, they were still on Carra Beanga Brook. They didn’t make the junction with Kanangra Creek until Monday and didn’t begin the long, 650-metre climb out until Tuesday, by which time they’d been reported overdue and the police and SES were on their way.

When police recovered the bodies on Wednesday morning, they were no longer on the ledge. They had somehow slipped off the ledge and fallen the last 10 metres into the shallow pool at the bottom.

The silence of the group still mystifies the canyoning community. Rick Jamieson, author of Canyons Near Sydney, the canyoning guidebook the party used, has updated the notes on Carra Beanga in the new edition to better warn of the risks he believed might have contributed to the tragedy. He’d been unable, he said, to find out the facts.

Until recently, the Newcastle University Mountaineering Club (NUMC) Web site made no mention of the club’s greatest tragedy, although it had a link to another site describing a near disaster on the same spot in the same canyon. Now, the NUMC site includes this acknowledgment of that terrible weekend, written by the vice-president, Steven Ahern:

‘Steve and Mark represented everything the club stands for. They loved life and they lived it to the fullest. They took what they had been given and did great things with it, often to the enjoyment of those around them. I know that they would love nothing more than to see the NUMC have another year enriched with the pleasures that the outdoors, our own company, and our adventures and sports provide for us.”

A tragedy of errors:

After completing the canyon trip, Good Weekend asked professional guide Lucas Trihey for his assessment of what might have happened. He said: “The major thing that struck me was how cold it was and consequently how quickly hypothermia would have set in for those guys who were wearing inadequate clothing and no wet-weather gear.

” … It’s surprising how quickly the hand muscles lose their strength when they get cold and numb. If Mark was trying to do something complicated like undo knots … then even mild hypothermia would have made it impossible very quickly.

“The real issue is that there seem to have been a series of minor errors which, taken together, meant that the group was in a poor position to handle an incident such as Steve’s accident while on the rope.” In Trihey’s view, the group started relatively late for such a long, remote canyon, and kept going after dark while underdressed for such cold and wet conditions.

“For such a large group,” he says, “there seemed to be too few experienced people capable of investigating the cause of the delay after Mark and Steve disappeared.”

Given that the group was tired and cold, darkness had fallen, and they were getting confused messages from the canyoners below, it isn’t hard to see why they decided to stay put and wait until morning broke.

So what are the lessons of the tragedy, according to Trihey? “There’s a fine line with this sort of trip between everything going well and having a major epic. Sometimes a seemingly minor incident can tip the balance.” To minimise the chances of problems on long, remote canyons, Trihey says these guidelines may help:

– A maximum group size of six for remote canyons means quicker (and safer) trips but still allows a healthy safety margin if someone is hurt.

– Allow plenty of time to get to the destination or to at least reach a safe place to spend the night.

– Thermal, fleece and quality waterproof clothing are essential for all trips.

– At least one member of the group should have done the trip before. A person with good technical skills and experience should be last down and should be equipped with gear (preferably including a spare rope) for rescue use.

Analysis: This accident was the culmination of a series of errors. The large group, including many beginners, attempted a challenging canyon in winter. They started far too late in the day. As a result, they were in the midst of the canyon when the sun set, forcing them to continue descending a challenging canyon with cold, fatigued, inexperienced people. It highlights how a series of small failings can lead to fatal consequences.

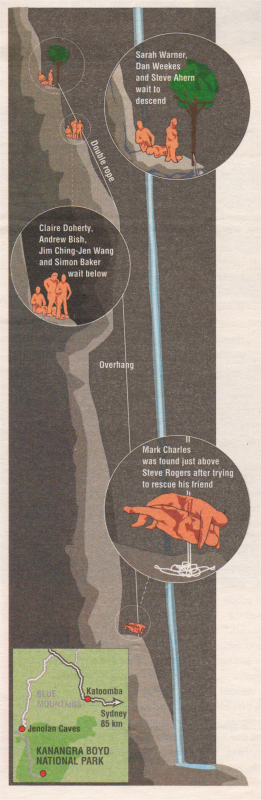

Diagram of abseilers